alt="Aquila’s Lex Raas: Driving the Cat Pack (Part 1)"/>

alt="Aquila’s Lex Raas: Driving the Cat Pack (Part 1)"/>

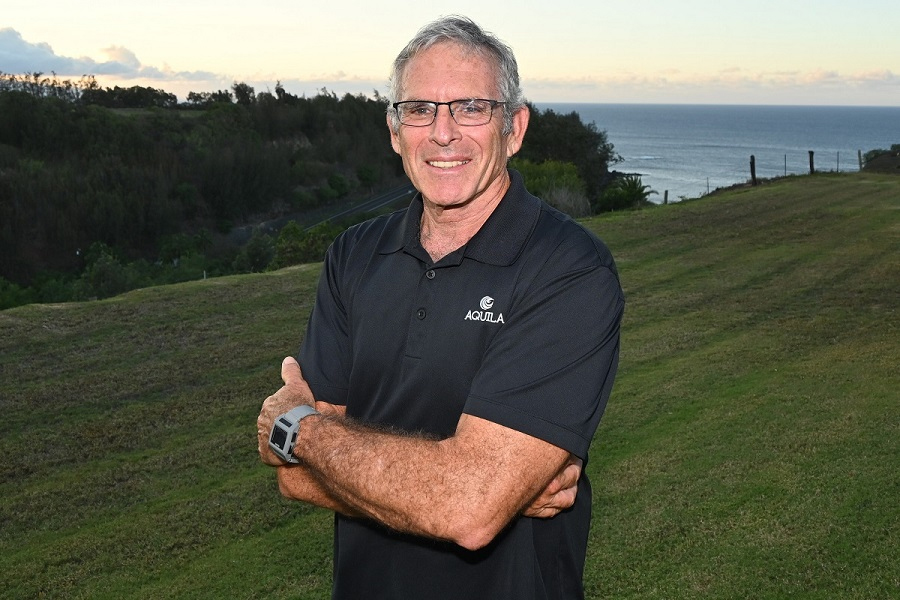

I grew up in South Africa, moved to France, then moved to the US, France and US again, and spend much of the year in Hawaii. We’ve dragged our kids through three continents, which has been fun and good for everybody, I believe.

I’ve been in the boating game all my life, really. My dad was very much into sailing and racing, so I grew up sailing and skiff rowing in South Africa. I dropped out of school and started building boats, building my first trimaran when I was 15. I’m now 65, so I’ve spent the last 50 years in the industry!

I went to college for a while and sort of finished up school, but didn’t enjoy it, so went back to building boats. My wife and I had a factory with about 80 staff. We were building small production sailboats, based on Quarter Ton Cup and Half Ton Cup, and I was also racing. In the early 1980s, we became the South Africa importer for Beneteau and that went so well that we shut down our own factory.

In 1984, sanctions were taking effect, there was a recession and by 1985 the exchange rates divided by three, so it was ‘game over’ for importing boats. One of my kids had finished high school, one was close and the other two were young, so it was time to think what we should do as a family. I saw the challenges in the future in South Africa for my kids.

I reached out to Beneteau and they said I’d have a job with them as soon as I got to France. I didn’t even have it in writing, but we took the kids over to France.

At that time, Beneteau was setting up its operation in the US (in Marion, South Carolina). I was about nine months into my job in France when they asked if I wanted to move to the States and I said, let’s go. A lot of my job was almost Americanising the brand, so I was able to learn a lot about the American market. There were significant differences, although there are less today.

The 44 Yacht has been Aquila’s best-selling model

I was CEO of Beneteau USA for a short while, then they asked me to take charge of the entire development office in France, so I went back and spent the last year-and-a-half of my eight years with Beneteau in this role. In those days, Beneteau was the trend-setter by a long shot, so it was a cool role.

I was selling Beneteau boats to The Moorings, so got to know them well. Because my kids were in high school and university, we wanted to go back to the US and The Moorings offered me a job in 1994. It was a more junior position, Logistics Director, which I’ve done a couple of times when moving companies – take a step down but look up at where we can go. I eventually became CEO and later oversaw the merger with Sunsail. I was with them until 2010, just after the global economic meltdown.

When I joined The Moorings, I oversaw purchasing the boats, specs and customer service. The Moorings had six or seven French-built catamarans. I had always been a bit of a multihull guy and thought catamarans was the way to go.

At that point, there was only a handful of catamarans in the Caribbean and I surveyed people who used them. Fundamentally, they loved catamarans, but they didn’t like certain aspects like the galley being below deck, the traveller in the cockpit and engines too small for when they wanted to motor upwind.

I realised catamarans were the future of charter, made a presentation to build some new designs and got the go-ahead from the Executive Committee. Then they asked who was going to build them. I needed to find a builder, but nobody was interested. I approached the big catamaran builders in France, but they wouldn’t make the changes I wanted, which included a big platform at the back, traveller on the top and a lot of other things that are normal on catamarans today.

In the end, I called up my buddy John Robertson in South Africa, where we had built some racing boats together and asked him if he was interested in building some cats. We talked and that’s how it started. The Moorings placed an order for 18 Leopards.

We launched the Moorings 4500 (Leopard 45) in 1997 and it won Boat of the Year straight out of the block and the huge growth in catamarans in The Moorings began. We went from cats making up a few per cent of our fleet to 60 per cent by the time I left in 2010. Sailing cats had been super niche, but now they’re mainstream.

That’s a fun story as well. At The Moorings, we started a power charter business called Nautic Blue. We bought some monohull motor yachts because we thought powerboat owners wouldn’t even think of power catamarans – there were no powercats back then. However, we had a lot of issues with reliability, props, shafts, because they just weren’t built for charter.

The interesting thing is that the boat would break down and we’d tell the customers they could use a sailing cat, but don’t put up the sails – just drive it. Then guys were coming back, saying, ‘Wow, we’re back next year! This is the best vacation we’ve had.’ And that was all because they’d been on a catamaran. So, then we just converted the sailboat hulls, added to a flybridge, and that’s how Leopard powercats started in 2005.

We changed the name Nautic Blue to Moorings Power. We originally chose Nautic Blue, a different brand, because we thought powerboaters and sailors don’t really mix, but that was rubbish. They do mix because they all just want to have a good time in the Caribbean. By the end of 2010, after 16 years, I left on a one-year non-compete clause and then started working for MarineMax.

We started MarineMax Vacations and Aquila at pretty much the same time. As MarineMax is a powerboat company, we decided to focus on building powercats because there were already a lot of sailing cats in the Caribbean and Leopard were the only real powercats. I was lucky to have the support of Bill McGill, co-founder and then-CEO and the father of current CEO Brett McGill.

We asked quite a few builders, but each said they didn’t see a future for powercats, so there I was again, looking for a builder. This time, we approached Sino Eagle because they had built some Leopards, so there was a relationship. I called Frank Xiong of Sino Eagle and put him together with Bill McGill and we started Aquila, with MarineMax placing some orders.

The Aquila 36 Sport became one of the best-selling motor yachts in the US of its size

On both occasions (starting Leopard and Aquila), if I hadn’t really believed in what I was doing, it could easily have not happened. However, I’ve been very fortunate in having great support each time. I’ve worked for the world’s biggest sailboat builder, the biggest charter boat business, now I work for the biggest boat retail business and all of them had incredible people to work with.

I could never have done what I’ve done without these people and CEOs like Bill McGill, who supported me even when there was a lot of opposition in the industry and sometimes internally. They’ve all changed their minds now. And I’m still here at MarineMax, heading development at Aquila and keeping the relationship with Sino Eagle on a strong footing.

I need to emphasise that the charter business is such a small piece of Aquila. We’ve probably only got about 20 or so boats in the MarineMax Vacations fleet, so charter is a tiny piece of our business compared to other catamaran builders.

The hugely popular Aquila 36 is available in multiple versions

The Aquila boats were really developed as private boats and adapted a bit for charter, the opposite to some other brands. What I quickly realised when I joined MarineMax is there is no better company to sell boats. They are amazing, ultra-professional. They have everything covered for a boat owner.

I always say, no stool stands on one leg. To have a successful business model in the boating industry, you need three legs: innovation, distribution and manufacturing. If any of those aren’t working, it’s not a long-term play. We’ve used J&J Design from the beginning and now we’ve expanded to other designers because we’re moving into different segments of the industry.

Aft view of two versions of the Aquila 36 Sport

The 44 Yacht was the first boat of that size with a full-beam master cabin, so that was a real breakthrough. The forward stairs from the flybridge to the foredeck became part of our DNA for the inboard boats and it’s so practical, so you see it on the new 54 Yacht and 70 Luxury.

Innovation is sometimes taking two good ideas and making them into a great idea. Quite often, a lot of the things I did, I wouldn’t say it was completely my idea. Probably someone has already done it, but they didn’t do the other three things that connected to it and brought it all together.

The 32 is currently Aquila’s entry-level Sport model

The aft bar connecting the cockpit and the galley was new when we started but is common now. Because you have so much room on cats, you need to create different places to hang out. Another feature I like is our steps from the swim platform. They’re high but if you turn around, you’ll see they’re big enough to use as seats and face the water. We have almost stadium seating at the back of the boat.

For our bigger boats, we have bulbs at the front of the hulls. Cats have quite narrow bows and carry a lot of weight due to the flybridge and hardtop. For example, the 44 is a relatively short boat with a lot of height. If you’re going into chop, the bulb creates an enormous amount of additional buoyancy, which dampens the motion, so all our inboard yachts have bulbs.

The Aquila 32 Sport was relaunched in 2021 with an extended hull, fixed swim platform plus new seating configuration and hardtop

Our next most popular boat was the 36, a fast outboard with two cabins; it’s like a crossover with motor yachts. It created a completely new position in the market and took a lot of market share against established monohull yacht brands in the US. We can’t build them fast enough.

We recently created the Cruiser version by adding aft sliding doors, so you can enclose the saloon. We now have three versions: the real sporty version with the low windscreen; the full-height windscreen with the back open, which I call ‘semi-sport’; and now the full windscreen with sliding door, like a proper cabin cruiser.