Lifestyle

Louis Vuitton Stars Football Icons Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo in “Victory is a State of Mind” Campaign

November 23, 2022

Lifestyle

La Fabrique Du Temp Louis Vuitton is a literal Factory creating New Perspectives of Time

February 18, 2021

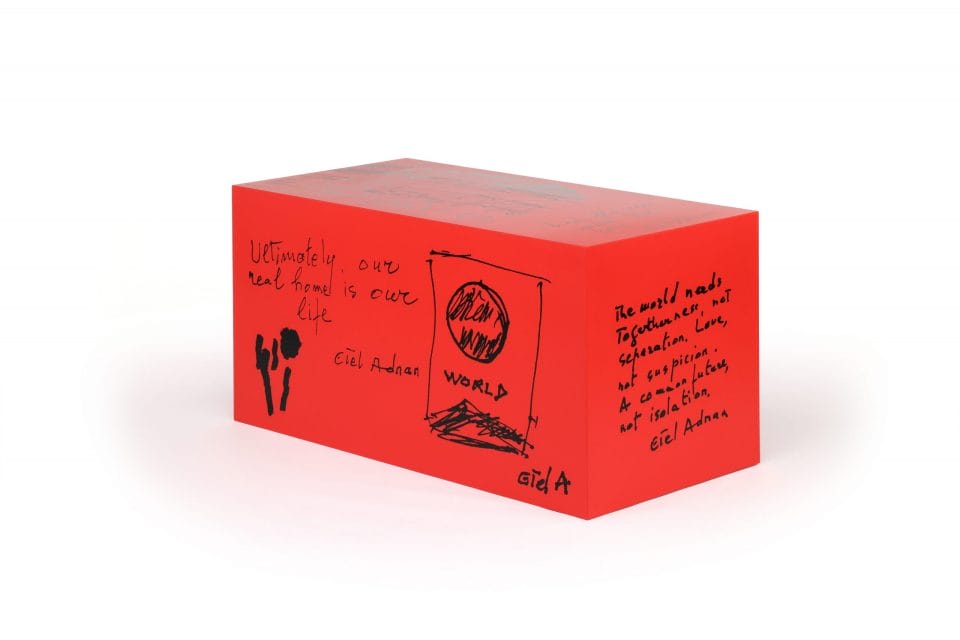

alt="Louis Vuitton showcases 200 trunks, 200 visionaries"/>

alt="Louis Vuitton showcases 200 trunks, 200 visionaries"/>

alt="Absolute signatures feature on 52 Fly"/>

alt="Absolute signatures feature on 52 Fly"/>

alt="Fraser Asia, Ferretti Group APAC sell Custom Line Navetta 30"/>

alt="Fraser Asia, Ferretti Group APAC sell Custom Line Navetta 30"/>